In the aftermath of the Mangalore crash, the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA, India) has brought out a number of circulars on aviation safety, even as investigations reveal that the pilot-in-command (PIC) of the ill-fated 737 was suffering from "sleep inertia".

A factor crucial to aviation safety, that could be easily overlooked is the physical and mental state of the pilot(s). In this context, it would be worthwhile making an effort to understand the following:

THE BIOLOGICAL HUMAN CLOCK

From the above diagram, the period between 02:00 and 06:00 (from the point of view of the human body) is characterized by low performance, low levels of alertness, low body temperature, and high fatigue. This is called the "window of circadian low". In most cases, the human body clock has conveniently chosen this period (in response to environmental conditions like sunlight, ambient temperature, etc) to "switch-off", as this is absolutely essential for its proper functioning.

Research done at the University of South Australia Sleep Research Center reveals that performance while fatigued is comparable to performance while intoxicated. Volunteers were subjected to judgment, reasoning, vigilance, and hand-eye coordination tests on two different occasions; on one occasion, after making them tired, and, on another occasion, after making them drunk. It was found that after 17 hours of wakefulness, at about 03:00, the effects of fatigue on performance were equal to a 0.05% blood alcohol concentration; and at 08:00 (about 22 hours of wakefulness), a performance impairment equivalent of 0.1% blood alcohol concentration was noted. In many states in the US, a blood alcohol concentration of 0.05% to 0.1% is enough to be arrested for DUI (driving under influence).

MICROSLEEP

When was the last time you "dozed off" in the middle of doing something ? That feeling of heaviness in the eyelids; that feeling of just letting go of things and surrendering to sleep, that nothing is more important in those few moments than getting your forty winks..........and at the same time, the feeling that you are still mindful of your job and everything seems to be looking good..........until suddenly, someone comes by and says that you have been nodding off, or your newspaper drops to the floor, or you fall off the chair !

The above mentioned "feelings" are cues/warning signs that you might soon experience bouts of microsleep, which are brief unintended episodes of loss of attention associated with events such as blank stares, head snapping, prolonged eye closure which may occur when a person is fatigued but trying to stay awake to perform a monotonous task. A microsleep is an episode of sleep that can last anywhere from a fraction of a second to several seconds and is often the result of sleep deprivation and mental fatigue. Microsleep is extremely dangerous in situations that demand constant alertness, primarily because people who experience microsleep usually remain unaware of them, and instead believe that they are indeed awake and have only just temporarily lost focus.

CUMULATIVE SLEEP DEBT

This is also something that could go unnoticed until it really begins to matter. We need about 8 hours of sleep per day, on average; now let's say that due to "commercial pressures", a pilot gets only 6 hours on Monday. On Tuesday, he again manages to squeeze in 6 hours, and on Wednesday, he gets only 5 hours. I have dared to assume that it is only a busy work schedule that has cost our pilot his sleep - NOT taking into account non-professional factors like staying up all night (for various reasons.....). By Thursday, he has lost almost a night's worth of sleep, and this is bound to show by way of degraded performance and physical fatigue, not to mention tendencies for microsleeps to occur.

An easy way in which sleep debt can build, is during flight operations on the back side of the clock, to which, particularly cargo pilots might be very susceptible. The human body is naturally programmed to sleep during certain hours (as mentioned earlier, the "window of circadian low" occurs between 02:00 and 06:00). When we try to override this, there are two consequences:

1. We are trying to stay awake, when the body wants to be sleeping.

2. We are trying to sleep, when the body wants to stay awake.

(2.) has the effect that even when we have the time to sleep (albeit during the day, when off-duty), we find it difficult to catch up on sleep, and even if we do, it is often inadequate. Frequent and extended occurrences of this sort would eventually result in cumulative sleep debt.

TIME SINCE AWAKENING

A proper night's sleep fully recharges your batteries, but as soon as you wake, energy slowly drains out as the day progresses. So it is equally important for a pilot to be aware of "time since awakening", and take care that it does not lead to cumulative sleep debt.

SLEEP INERTIA

It seems to have happened to the pilots involved in the recent air crash (Air India Express Flight IX 812, Boeing 737NG) at Mangalore. Sleep inertia is a physiological state immediately following a sudden awakening (from sleep) and is characterized by a decline in motor dexterity, accompanied by feelings of lethargy and grogginess, and a tendency to want to return to sleeping. Sleep inertia can be more severe when a person is awoken from deep sleep due to fatigue/sleep debt.

PREVENTIVE MEASURES AND PRECAUTIONS

AWARENESS - Know how much sleep you ideally need to be able to perform well. Also know how long you can keep up the good work before performance begins to degrade and you need to take rest.

PLANNING - The earlier you know your fixtures for the week (or month), the better you can plan how you are going to distribute your sleep during those periods. It would also help to plan for changes in sleep patterns early on, instead of at the last minute.

HEALTHY LIFESTYLE - A healthy lifestyle with lots of exercise and eating nutritious food will go a long way in regulating how much sleep the body needs. It is needless to mention the ways in which exercise and a good diet are invaluable to health. The human body clock seems to suggest that the best time for exercise would be late in the evening.

AWARENESS BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER FLIGHT OPERATIONS

CAFFEINE - A hot cup of coffee is the perfect stimulant to stay awake. Take note though, that caffeine takes about half an hour to kick into action, and its effect can last for about 3-4 hours.

For non-coffee drinkers, energy drinks can be a good alternative. However, the amount of caffeine in energy drinks is much less than that in coffee, so more amounts of energy drinks will have to be consumed.

Caffeine fights sleep, so any over-consumption of caffeine will also prevent a well deserved rest after a long flight. It would a good idea to be well-stocked with high-caffeine drinks on every flight, just to play it safe.

MELATONIN - Melatonin is a chemical produced by the pineal gland in the brain, and it has a function in regulating the human biological clock (circadian rhythm). Today, while it is available as a prescription-free, over-the-counter medication in the US, it is also illegal in many countries.

It would be wise to refrain from using this medication as much as possible, even though studies have shown that there are no side-effects due to to the short-term use of this drug. It is a drug, which is used to treat sleeping disorders, and should not be used as a preventive measure, especially without consulting a doctor. Studies have also shown that Melatonin can cause drowsiness, so it must be treated with extreme caution.

BEFORE A FLIGHT - Always be sensitive and aware of your "charge status". In most cases, people are not accurate when they "think they are doing okay" (which is why there are limitations on flight duty time); cues to watch out for are easy irritability and degradation in performance even for simple tasks, mood changes, slower reaction time, weaning concentration, judgmental errors, etc. It is more important (and harder) not to brush away these things. It is good to have an I'M SAFE checklist, if not a better personal checklist.

I - Illness, M - Medication, S - Stress, A - Alcohol, F - Fatigue, E - Emotion (I'M SAFE)

UNEXPECTED DELAYS - It would be wise to anticipate your sleep situation when a prolonged delay occurs, as your situation in the cockpit would be well different from what it would have been a number of hours earlier. A complete assessment from the point of view of safety during the approach and landing phases should be made - commercial pressures can force a fatigued pilot to make a decision which he probably wouldn't make under normal (well-rested) circumstances. Bear in mind that you might be most vulnerable to "get-home-itis" at this stage. As always, keep that shot of caffeine handy.

POST FLIGHT - If a situation arises where you are just unable fall asleep (because you are not yet used to sleeping during that part of the day/night), it is better to try and do some sleep inducing activity (like reading a boring book) and get just a few hours of sleep, rather than struggle in bed for a whole eight hours. Exercise, if done within a couple of hours before sleep, will only disrupt it, as does a heavy meal.

The more complicated a task (let alone multi-tasking), the more fatigued the body gets in trying to deal with it.

I hope the observations made here help the hardest part of flying a little bit easier. Take care and fly safe !

For a further reading on pilot performance in relation to sleep, refer to the article below:

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0UBT/is_5_15/ai_69706945/?tag=content;col1

To read more about the FAA's new rules proposed to fight pilot fatigue, refer to the following article:

http://aircrewbuzz.com/2010/09/new-science-based-rules-for-mitigating.html

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Survival of the leanest (and meanest ?).

BOEING 737-100/200 vs. DASSAULT MERCURE

The Boeing 737-100 entered service in 1968 and was the smallest variant of the 737 series. The 737-200 was an extended-fuselage replacement for the 737-100. There are no 737-100s in service today. The 737-200s are also being phased out due to poor fuel efficieny, high noise emissions, and high maintenance and operating costs, but quite a few are still used in "second tier" and cargo operations. Later versions of the 737 (300/400/500/600/700/800/900) with better performance and fuel efficiencies are still with the airlines, making the 737 a huge commercial success for Boeing.

The Dassault Mercure was touted as a replacement for the Boeing 737 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9. It was, in fact, the worst failure of a commercial airliner in terms of number of aircraft sold, mainly due to its low operating range. Extremely modern tools for the time were used for the development of the Mercure. The Mercure was larger and faster than the 737, and was certified for CAT3A all-weather automatic landing. Air Inter, a French domestic air carrier, was the only airline that purchased these aircraft (about 10). An attempt to develop a Mercure-200 with better performance was abandoned due to lack of financing. All Mercures were retired from service in 1995, with an impressive 360,000 flight hours, 44 million passengers carried in 440,000 flights, no accidents, and a 98% in-service reliability.

The Boeing 737-100 entered service in 1968 and was the smallest variant of the 737 series. The 737-200 was an extended-fuselage replacement for the 737-100. There are no 737-100s in service today. The 737-200s are also being phased out due to poor fuel efficieny, high noise emissions, and high maintenance and operating costs, but quite a few are still used in "second tier" and cargo operations. Later versions of the 737 (300/400/500/600/700/800/900) with better performance and fuel efficiencies are still with the airlines, making the 737 a huge commercial success for Boeing.

|

| Boeing 737-100 |

|

| Dassault Mercure-100. Note the Pratt & Whitney JT8D powerplant, also used on the 737-100/200. |

Sunday, August 22, 2010

Across the pond

The North Atlantic is the busiest oceanic airspace in the world, with more than 370,000 crossings annually. With limited availibility of direct controller-pilot communications and non-availibility of radar surveillance, the structure of airspace in this region is influenced by a number of factors, including passenger demand, time-zone differences, effects of jet streams, weather, and restrictions on night flying.

Perhaps the most important of all these is the effect of jet streams, which are fast-moving currents of air situated in the tropopause, at a height varying from about 4 miles at the poles (polar jet stream) to about 8 miles at lower latitudes (sub-tropical jet stream). The width of a jet stream is usually a few hundred miles and its vertical thickness, often less than three miles. The winds within a jet stream can be very strong, ranging from about 90 knots, to over 200 knots.

The polar and sub-tropical jet streams are upper-level jet streams, occuring very near the tropopause, and their postions over the earth change every day, owing to pressure and temperature variations. In general, the upper-level jet streams may be said to "follow the sun", ie. they move northwards (to higher latitudes) during summer and southwards (to lower latitudes) during winter. Due to this daily variation in position, shape, and altitude at which jet streams occur, favourable paths across the North Atlantic accordingly vary on a daily basis.

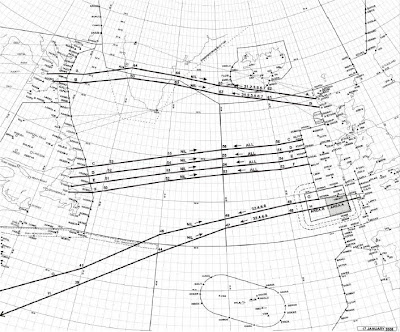

NORTH ATLANTIC (NAT) ORGANIZED TRACK SYSTEM (OTS)

The North Atlantic tracks are air routes that are published daily, taking into consideration the varying nature of the jet streams. As much as the jet streams significantly reduce flight duration (and fuel burn) for east-bound flights, they increase flight duration (and fuel burn) for west-bound flights. Air routes are optimized for minimum time, by chosing those routes that have maximum tailwinds and minimum headwinds. East-bound and west-bound routes are published daily by Shanwick Centre (EGGX) and Gander Center (CZQX) respectively, in consultation with adjacent oceanic area control agencies (OACs). Due consideration is given to airlines' preferred routing and airspace restrictions such as danger/military areas while planning these routes. Passenger demand and time-zone differences have resulted in two major sets of daily routes being published, a west-bound flow departing Europe in the morning, and an east-bound flow departing North America in the evening.

|

| Day-time west-bound tracks published by Shanwick Center (EGGX). |

|

| Night-time east-bound tracks published by Gander Center (CZQX). |

The above mentioned system of air routes that are published daily is also called "Organized Track System" (OTS), and is just one of the many air routes within/adjacent to the NAT airspace, such as the "Blue Spruce" routes and the North American routes (NARs).

|

| Other routes within the NAT airspace that are not part of the Organized Track System (OTS). |

MINIMUM NAVIGATION PERFORMANCE SPECIFICATIONS (MNPS)

With the non-availibility of radar surveillance and limited direct controller-pilot communications over the NAT, aircraft separation assurance and safety is ensured by requiring exacting standards of horizontal and vertical navigation performance and operating discipline. For this reason, the organized track system has been designated as MNPS airspace, and all flight operations that are intended to be carried out in such airspace are first required to be approved with respect to navigational/other equipment capabilities, their installation and maintenance procedure, aircrew training and qualifications, etc. by the state regulatory authority. Formal monitoring programmes are undertaken to quantify the achieved performances and compare them with standards required to ensure that established Target Levels of Safety (TLS) are met. If a deviation is identified, follow-up action after the flight is taken, both with the operator as well as the state of registry of the aircraft, to ascertain the cause of the deviation and to confirm further operability in MNPS airspace.

Currently, MNPS airspace extends vertically between FL285 and FL420 (in terms of normal cruising levels, FL290 to FL410 inclusive). MNPS airspace falls under RVSM (Reduced Vertical Separation Minimums) airspace and cruising flight levels are separated vertically by 1000 feet.

The lateral dimensions of MNPS airspace include the following control areas:

REYKJAVIK, SHANWICK, GANDER, and SANTA MARIA OCEANIC plus that portion of NEW YORK OCEANIC north of 27 deg. N and excluding the area west of 60 deg. W and south of 38 deg. 30 min. N. The diagram given below describes the lateral extent of the NAT MNPS airspace:

|

| Lateral extent of NAT MNPS airspace. |

FLYING IN NAT MNPS AIRSPACE

NAVIGATION

Unlike navigation over land, where there are sufficient ground navigation facilities like VORs and NDBs at reasonable distances apart, using which position checks can be made, navigation over the ocean is quite different, and requires long range navigatonal aids like global navigation satellite systems (GNSS - GPS navigation, for all practical purposes). Lack of radar coverage implies that the controllers will have to rely on position reports sent from the aircraft in order to maintain separation and manage traffic flow across the routes.

The defining waypoints of OTS tracks are specified by whole degrees of latitude and, using an effective 60 NM lateral separation standard, most adjacent tracks are separated by only 1 deg. of latitude at each 10 deg. meridian. It is therefore imperative that MNPS include technical navigation accuracy to be maintained and monitored. The NAT MNPS requires that the lateral track deviation error is less than 6.3 NM on either side of course (or 12.6 NM total lateral track error), for 95 % of the time. Even before the advent of GPS, the equipment on board most commercial aircraft achieved exceeded this requirement, with standard track deviations of about 2 NM.

Today, in the NAT airspace system, the predominant source of aircraft positioning is that of GPS. This includes aircraft that use stand-alone equipment as well as aircraft that have an integrated navigation solution (GPS + IRS, etc). The accuracy of GPS is such that the flight paths of any two GPS equipped aircraft navigating to a common point will almost certainly pass that point within less than a wingspan of each other !

COMMUNICATIONS

Most NAT air-ground communications use single side-band high frequency (HF) radio communications. Pilots communicate with oceanic area controllers (OAC) via aeradio stations staffed by communicators who have no executive ATC authority. Messages are relayed from the ground station to the air traffic controllers in the relevant OAC for action. In the NAT, there are six aeronautical radio stations, one associated with each of the oceanic control areas (OCAs). They are BODO RADIO (Norway, Bodo ACC), GANDER RADIO (Canada, Gander OACC), ICELAND RADIO (Iceland, Reykjavik ACC), NEW YORK RADIO (USA, New York OACC), SANTA MARIA RADIO (Portugal, Santa Maria OACC), and SHANWICK RADIO (Ireland, Shanwick OACC). The aeradio stations and the OACs are not necessarily co-located. Twenty-four HF frequencies have been allocated, in bands ranging from 2.8 Mhz to 18 Mhz, for communications in the NAT region. Due to diurnal variation in the intensity of ionisation in the refractive layers of the atmosphere, higher frequencies (greater than 8 Mhz) are chosen for communications during the day, and lower frequencies (less than 7 Mhz) are chosen at night. An aircraft on a trans-atlantic flight is generally allocated a primary and secondary HF frequency when it receives its clearance from domestic controllers shortly before entering oceanic airspace. Even with more advanced communications technology in the cockpit, like datalink communications (CPDLC) and satellite communications (SATCOM), carriage of HF equipment on board is always recommended (and is sometimes mandatory in some oceanic areas, like Shanwick OACC). Selective Calling (SELCAL) provides for the aircrew to be alerted by controllers, if and when necessary, and relieves the aircrew of having to maintain a listening watch on the communications frequency.

|

| Major World Air Route Areas (MWARA) HF radio frequency coverage in the NAT region. |

An often encountered problem with HF communications is poor radio wave propagation (due to ionospheric disturbances), also know as "HF black-out", in which case the aircrew follow established rules and procedures for radio communications failure, like for example, relaying messages on a VHF frequency, with the help of a nearby aircraft/radio station, or landing at a nearby airport. Today, with more aircraft being equipped with modern technology like SATCOM, HF black-out seems to be less of a safety issue as it has been in previous years.

PREFLIGHT

Assuming that all required equipment is certified and working properly, it has to be ensured that the Inertial Reference System (IRS) is accurately aligned before flight, and that the actual position of the aircraft, at alignment, is set into the system - failing which systematic errors will be introduced. While inserting waypoints into the flight computers, aircrew must verify the latitude and longitude co-ordinates with an accurate "master-document" in order to avoid gross navigation errors. In fact, special training is required in the insertion of way-points for MNPS operations, with relevant cross-checks being performed by the aircrew to ensure accuracy of the information being input.

INFLIGHT

During the initial part of the flight, ground based navigational aids are used to check the accuracy of the long range navigational systems (LRNs). It would be very unwise to continue the flight if very large "map shifts" are found to occur. Aircrew must be trained and familiar with receiving oceanic clearances. Routine navigational accuracy checks must be performed, and position reports made when necessary. Sometimes, meteoroligical reports might be required to be made to ATC, like for example, winds and outside air temperature.

Even though ATC clearances are designed to ensure that separation and safety standards are continually maintained, error do occur. Gross navigation errors (caused by mistakes in entering waypoints) are made, and aircraft are sometimes flow at flight levels other than those assigned by the controller. Consequently, it has been determined that allowing aircraft to fly self-selected lateral offsets during oceanic flights, will provide additional safety margins and mitigate the risk of traffic conflicts, should non-normal errors (such as navigation errors, flight-level deviation errors, or turbulence induced altitude changes) occur. These procedures are termed "Strategic Lateral Offset Procedures" (SLOP) and collision risks are significantly reduced by applying these offsets.

The magnetic compass is rendered unuseable, when flying close to the earth's north magnetic pole. Within NAT MNPS airspace, the northwest of Greenland, and also some parts of Canadian airspace, are areas of compass unreliability. Enroute charts show these areas, and basic inertial navigation systems require no special procedures here. However, special aircrew training may be required for flight operations in these areas.

Very long range operations might include the use of relief crew. It must be ensure that crew change does not interfere with the continuity of the flight, especially in the handling and treatment of navigational information.

POST FLIGHT

On completion of a trans-atlantic flight, navigational equipment is checked for errors, and follow-up action is taken as required.

ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT REQUIREMENT

Depending on the flight operation, aircraft may need to be equipped with Aircraft Collision Avoidance Systems (ACAS/TCAS), have dual long-range navigation systems (LRNs), and other such equipment in the interest of safety.

Click here for a more comprehensive reading on NAT MNPS.

Monday, August 2, 2010

Does a heavier airplane descend quicker than a lighter one ?

It is not uncommon for air traffic control (ATC) to issue a descent clearance at a particular airspeed. A very interesting question here is, given two identical airplanes, one loaded to full capacity and the other almost empty, which one would have a greater rate of descent for a given true airspeed ?

Consider two identical Boeing 737s, one heavy and the other light.

For any given angle of attack, the heavier plane would have to fly at a greater speed in order to generate more lift to maintain level flight. This is evident from the lift equation, given below:

Total Lift L = 0.5 * Cl * p * S * v^2, where

Cl - coefficient of lift that corresponds to a particular angle of attack

p - density of the medium, in this case air

S - Effective area of the wing that contributes to generating lift

v - velocity of air flow over the wing, which can be approximated to True Air Speed (TAS)

The gradient of descent, or the horizontal distance gained per foot of altitude lost depends on the ratio of lift-to-drag, and is greatest (gives the maximum range for a given loss of altitude) when the lift-to-drag ratio is maximum. This condition (maximum lift-to-drag ratio) occurs at a particular angle of attack, for a given type of wing/airframe, and does not depend on the weight of the aircraft.

However, the AIRSPEED at which this given angle of attack occurs DOES vary with the weight of the aircraft, as it was seen that more lift is required for heavier weights, and this lift can be generated by flying at a higher airspeed. Consequently, the maximum "glide" range for the heavy 737 will be the same as for the light 737, PROVIDED that the heavy 737 is flown at a higher airspeed to give the same angle of attack which gives the maximum lift-to-drag ratio. The heavy 737, flying at its higher minimum drag speed, will come down faster than the light 737, flying at its lower minimum drag speed , but both planes will travel the same ground distance for a given altitude loss.

Now, to answer the question. Assume that the heavy 737 has a minimum drag speed of about 240 knots, and the light one, about 210 knots. If ATC issues a clearance to descend at 200 knots, then the light 737 will follow the green gradient line (above), and the heavy 737 will follow the red gradient line. The heavy 737 will not cover as much ground distance for a given altitude drop as the light 737 and it will come down much quicker than the light 737.

On the other hand, if ATC issues a descent clearance at 250 knots (as is more often the case), the heavy 737 will follow the green gradient line, and the light 737 will follow the red gradient line. This time, not only will the heavy 737 cover more distance for a given altitude drop (or drop less altitude for a given ground distance) than the light 737, it will also take longer to come down.

It can be concluded that, for airplanes with similar glide characteristics, but different weights, the airplane whose minimum drag speed most closely matches the descent clearance airspeed will be the one that has the most shallow descent gradient (green gradient line) and will take longer to come down; all the others will have a steeper descent gradient (red gradient line) and will come down faster.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Engines Turn Or Passengers Swim !

Prior to the 1960's, there existed something called the "60 minute rule" for twin-engined aircraft. The rule stated that, in simple terms, the flight path of a twin-engine airplane should not be more than 60 minutes away from a suitable emergency airport. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), keeping in mind the limitations of the piston-engine, had in 1953, introduced this rule to enhance safety during long-distance twin-engine flights, as they were considered very risky. The downside to this rule was, for a twin-engine flight to take place between two airports at a considerable distance apart, there had to be sufficient emergency airports at most 60 minutes away from any point along the way. This very often resulted in twin-engined flights having to follow a "staggered" flight path, just to stay within the 60 minute diversion period. Many routes were off-limits to twin-engine operations, simply because there weren't sufficient 60 minute diversion points available enroute, and these routes were called exclusion zones.

RISE AND FALL OF THE TRI-JETS

By the 1960's, it was evident that jet engines had higher thrust and were more reliable than piston-engines available during that period. In 1964, the 60 minute rule was waived for three-engined jet airplanes. However, the twin-engined jet airplanes were still restriced to the 60 minute diversion period. This led to the development of intercontinental jets like the Boeing 727, Lockheed L-1011 Tristar, and the McDonnell Douglas DC-10.

The 60 minute rule was an FAA mandate intended for twin-engine operations within the United States. Twin-engine operations in other parts of the world, especially in European countries, were subject to the ICAO's "90 minute rule", which required a less stringent 90 minute diversion period. This time relaxation was exploited by Airbus, and the world's first high-bypass turbofan engine widebody airliner, the Airbus A300, entered service in 1974. The A300 could carry just about as many passengers as far as the DC-10, and was 30 percent more fuel efficient than the Tristar. Very soon, the A300 was certified for extended range operations over water, providing for more flexibility in routing (outside the US). In America, airlines like Pan Am and Eastern began inducting A300s into their fleet as a replacement for existing tri-jets, owing to their higher fuel efficiency and better performance. By 1981, Airbus was growing rapidly, having sold over 300 aircraft to more than forty airlines worldwide - and Boeing rolled out the 767.

In May 1985, for the first time, the FAA extended the 60 minute diversion period to 90 minutes, for TWA's Boeing 767 service between St. Louis and Frankfurt. In fact, a little later, this was further extended to 120 minutes. And so it was, that the first "Extended Range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards" or ETOPS "rating" was applied to a twin-engine airplane. In this particular case, the rating was called an ETOPS-120 rating, in keeping with the 120 minute diversion period. As airplane engines became more reliable with technological advancement, the ETOPS-180 rating was soon approved, in 1988, by the FAA, subject to the engine meeting very high technical standards and qualifications, and twin-engine airplanes like the Boeing 737, 757, 767, and the Airbus A300 were ETOPS certified. This brought an end to the intercontinental tri-jets, which by now, were relatively more uneconomical to the company.

ETOPS RATINGS AND CERTIFICATIONS

ETOPS certification consists of an ETOPS "type approval" and an ETOPS "operational certification".

1. ETOPS type approval consists of certifying the engine/airframe combination on the basis of tests conducted to meet such standards as prescribed by the ETOPS requirements. These tests are conducted during the type certification of the airplane, and may involve shutting down an engine and flying the entire diversion time on the remaining engine, very often over the middle of oceans. It must be demonstrated that, during the diversion period, the flight crew is not unduly burdened by excess workload due to the lost engine, and the probability of the remaining engine also failing is extremely remote.

2. ETOPS operational certification refers to the certification of the operator (eg. airline) to conduct ETOPS flights, having satisfied regulatory requirements pertaining to training and qualification of flight crew in ETOPS procedures, as well as experience in conducting ETOPS operations. For example, an airline with extensive experience in long distance operations may be granted immediate ETOPS approval by the regulatory authority, compared to a relatively less experienced airline which may have to be put through a number of certification tests before being granted ETOPS approval.

Under current regulations, the following ETOPS ratings may be awarded:

ETOPS-75

ETOPS-90

ETOPS-120/138

ETOPS-180/207

Approval for ETOPS is granted in cautious increments, to allow airlines to build in-service experience and expertise in operating over extended routes with a particular airframe-engine combination. An airline (to be more specific, one or more aircraft in the fleet) is normally granted ETOPS approval in increments of 75, 120, and 180 minutes. For example, an airline seeking ETOPS-120 approval must first prove that it is capable of successfully operating under ETOPS-75 for a year, before being granted ETOPS-120. One of the important parameters that is considered during ETOPS certification is the in-flight shutdown (IFSD) rate, which represents the number of engine shutdowns per 1000 hours of operation, all engines in service (for a particular engine-airframe combination) put together. For example, one in-flight shutdown in an airline fleet logging 50,000 hours would be represented by an IFSD of 0.02 failures per 1000 hours of operation. To gain ETOPS-180 approval, an air carrier must operate its extended range fleet for at least one year in extended range operations, recording an IFSD of 0.02 per 1000 hours. Any increase in IFSD would be grounds for re-evaluation by the regulator, of the capability of the air carrier to safely conduct ETOPS operations.

ETOPS TODAY

In 1988, the FAA ammended the ETOPS regulations to extend the 120 minute diversion period to 180 minutes, subject to stringent techical and operational qualifications. This made 95 percent of the earth's surface available for ETOPS operations. In European countries, the JAA extended the 120 minute diversion to 138 minutes (15 percent more) to take into account the non-availibility of some of the emergency diversion airports during winter/bad weather, thereby allowing airlines to operate across the North Atlantic under less stringent (and less expensive) ETOPS-120/138 rules, instead of ETOPS-180. Similarly, in 2000, the FAA approved some air carriers for ETOPS-180/207 (a 15 percent extension to the 180 minute diversion period) on certain routes during unfavourable weather conditions over the North Pacific, considering the non-availibility of sufficient emergency airports.

For further reading on the FAA's new ETOPS rules (2007) click here.

In 1995, the Boeing 777 was the first airliner to have an ETOPS-180 rating on entry into service, and in 2009, the Airbus A330 became the first airliner approved for ETOPS-240 operations on entry into service, opening up new routes in the South Pacific, South Atlantic, and Southern Indian oceans, to twin-engine operations. Aviation regulatory authorities worldwide are now working towards having common extended-range standards that would also include all three and four engine civil airliners, under a new system that will be called Long Range Operational Performance Standards (LROPS).

RISE AND FALL OF THE TRI-JETS

By the 1960's, it was evident that jet engines had higher thrust and were more reliable than piston-engines available during that period. In 1964, the 60 minute rule was waived for three-engined jet airplanes. However, the twin-engined jet airplanes were still restriced to the 60 minute diversion period. This led to the development of intercontinental jets like the Boeing 727, Lockheed L-1011 Tristar, and the McDonnell Douglas DC-10.

| |

| Boeing 727 |

|

| Lockheed L-1011 Tristar |

| ||

| McDonnell Douglas DC-10 |

|

| Hawker Siddely Trident |

The 60 minute rule was an FAA mandate intended for twin-engine operations within the United States. Twin-engine operations in other parts of the world, especially in European countries, were subject to the ICAO's "90 minute rule", which required a less stringent 90 minute diversion period. This time relaxation was exploited by Airbus, and the world's first high-bypass turbofan engine widebody airliner, the Airbus A300, entered service in 1974. The A300 could carry just about as many passengers as far as the DC-10, and was 30 percent more fuel efficient than the Tristar. Very soon, the A300 was certified for extended range operations over water, providing for more flexibility in routing (outside the US). In America, airlines like Pan Am and Eastern began inducting A300s into their fleet as a replacement for existing tri-jets, owing to their higher fuel efficiency and better performance. By 1981, Airbus was growing rapidly, having sold over 300 aircraft to more than forty airlines worldwide - and Boeing rolled out the 767.

| ||

| Airbus A300 |

|

| Boeing 767 - Note the striking similarity in design to the A300. |

In May 1985, for the first time, the FAA extended the 60 minute diversion period to 90 minutes, for TWA's Boeing 767 service between St. Louis and Frankfurt. In fact, a little later, this was further extended to 120 minutes. And so it was, that the first "Extended Range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards" or ETOPS "rating" was applied to a twin-engine airplane. In this particular case, the rating was called an ETOPS-120 rating, in keeping with the 120 minute diversion period. As airplane engines became more reliable with technological advancement, the ETOPS-180 rating was soon approved, in 1988, by the FAA, subject to the engine meeting very high technical standards and qualifications, and twin-engine airplanes like the Boeing 737, 757, 767, and the Airbus A300 were ETOPS certified. This brought an end to the intercontinental tri-jets, which by now, were relatively more uneconomical to the company.

|

| The Tupolev Tu-154 is one of the few commercial tri-jet airliners still in service. |

ETOPS RATINGS AND CERTIFICATIONS

ETOPS certification consists of an ETOPS "type approval" and an ETOPS "operational certification".

1. ETOPS type approval consists of certifying the engine/airframe combination on the basis of tests conducted to meet such standards as prescribed by the ETOPS requirements. These tests are conducted during the type certification of the airplane, and may involve shutting down an engine and flying the entire diversion time on the remaining engine, very often over the middle of oceans. It must be demonstrated that, during the diversion period, the flight crew is not unduly burdened by excess workload due to the lost engine, and the probability of the remaining engine also failing is extremely remote.

2. ETOPS operational certification refers to the certification of the operator (eg. airline) to conduct ETOPS flights, having satisfied regulatory requirements pertaining to training and qualification of flight crew in ETOPS procedures, as well as experience in conducting ETOPS operations. For example, an airline with extensive experience in long distance operations may be granted immediate ETOPS approval by the regulatory authority, compared to a relatively less experienced airline which may have to be put through a number of certification tests before being granted ETOPS approval.

Under current regulations, the following ETOPS ratings may be awarded:

ETOPS-75

ETOPS-90

ETOPS-120/138

ETOPS-180/207

Approval for ETOPS is granted in cautious increments, to allow airlines to build in-service experience and expertise in operating over extended routes with a particular airframe-engine combination. An airline (to be more specific, one or more aircraft in the fleet) is normally granted ETOPS approval in increments of 75, 120, and 180 minutes. For example, an airline seeking ETOPS-120 approval must first prove that it is capable of successfully operating under ETOPS-75 for a year, before being granted ETOPS-120. One of the important parameters that is considered during ETOPS certification is the in-flight shutdown (IFSD) rate, which represents the number of engine shutdowns per 1000 hours of operation, all engines in service (for a particular engine-airframe combination) put together. For example, one in-flight shutdown in an airline fleet logging 50,000 hours would be represented by an IFSD of 0.02 failures per 1000 hours of operation. To gain ETOPS-180 approval, an air carrier must operate its extended range fleet for at least one year in extended range operations, recording an IFSD of 0.02 per 1000 hours. Any increase in IFSD would be grounds for re-evaluation by the regulator, of the capability of the air carrier to safely conduct ETOPS operations.

ETOPS TODAY

In 1988, the FAA ammended the ETOPS regulations to extend the 120 minute diversion period to 180 minutes, subject to stringent techical and operational qualifications. This made 95 percent of the earth's surface available for ETOPS operations. In European countries, the JAA extended the 120 minute diversion to 138 minutes (15 percent more) to take into account the non-availibility of some of the emergency diversion airports during winter/bad weather, thereby allowing airlines to operate across the North Atlantic under less stringent (and less expensive) ETOPS-120/138 rules, instead of ETOPS-180. Similarly, in 2000, the FAA approved some air carriers for ETOPS-180/207 (a 15 percent extension to the 180 minute diversion period) on certain routes during unfavourable weather conditions over the North Pacific, considering the non-availibility of sufficient emergency airports.

For further reading on the FAA's new ETOPS rules (2007) click here.

In 1995, the Boeing 777 was the first airliner to have an ETOPS-180 rating on entry into service, and in 2009, the Airbus A330 became the first airliner approved for ETOPS-240 operations on entry into service, opening up new routes in the South Pacific, South Atlantic, and Southern Indian oceans, to twin-engine operations. Aviation regulatory authorities worldwide are now working towards having common extended-range standards that would also include all three and four engine civil airliners, under a new system that will be called Long Range Operational Performance Standards (LROPS).

|

| Boeing 777 |

|

| Airbus A330 |

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Arrivals into Heathrow - The Holding Stack

London's Heathrow airport is the fifth busiest airport in the world in terms of total passenger traffic (67 million annual passengers, approximately), and handles nearly 700 landings each day. It is located about 12 nautical miles west of central London, and has two parallel east-west oriented runways (there were six shorter runways earlier, arranged in three pairs at different angles, but this arrangement has now been done away with). Most of the time, airplanes landing at Heathrow have to fly over the city, due to the nature of prevailing winds, which generally require an approach from east to west (a landing on the west-facing runway). On days on which the winds favour the use of the east-facing runway, the airplanes climb out over the city, before proceeding on course. This, in recent years, has raised concerns about air pollution, safety, noise pollution, and the impact of Heathrow on its surroundings.

Normally, airplanes arriving into Heathrow are directed by controllers to one of four holding "stacks", each located over a navigation beacon. These navigation beacons, and hence the holding stacks, are located at Bovingdon, Lambourne, Ockham, and Biggin, all on the outskirts of London. Sometimes, depending on traffic load, airplanes may first be directed to an "outer stack" (eg. Daventry), before proceeding to one of the above "inner stacks".

Arrivals are first directed to the top of the stack until controllers are able to clear traffic in lower layers of the stack. As lower levels of the stack clear up, airplanes holding at higher levels are moved down in sequence. The height and number of levels in each stack, and the number of stacks in use all depend on how busy the terminal environment is and the pattern of arrivals into the terminal area. The lowest level will be at least 7000 feet above the ground, and adjacent levels are separated by a minimum of 1000 vertical feet. Traffic and other factors permitting, controllers will vector the aircraft onto the final approach course when the aircraft reaches an appropriate altitude/level in the stack.

As mentioned earlier, there have been environmental concerns regarding the current system of handling arrivals into Heathrow. While there have been some organizations that have suggested measures like banning night flights, altering flight paths, extending runways, reducing the number of short-haul flights, and imposing passenger duty on transfer passengers, there have been others that have proposed changes to airspace management and handling procedures.

|

| Heathrow is about 12 nautical miles to the west of central London. |

| |||||

| Location of "inner stacks" at Bovingdon, Lambourne, Ockham, and Biggin. |

Arrivals are first directed to the top of the stack until controllers are able to clear traffic in lower layers of the stack. As lower levels of the stack clear up, airplanes holding at higher levels are moved down in sequence. The height and number of levels in each stack, and the number of stacks in use all depend on how busy the terminal environment is and the pattern of arrivals into the terminal area. The lowest level will be at least 7000 feet above the ground, and adjacent levels are separated by a minimum of 1000 vertical feet. Traffic and other factors permitting, controllers will vector the aircraft onto the final approach course when the aircraft reaches an appropriate altitude/level in the stack.

|

| Leaving the stack for final approach course and landing. |

As mentioned earlier, there have been environmental concerns regarding the current system of handling arrivals into Heathrow. While there have been some organizations that have suggested measures like banning night flights, altering flight paths, extending runways, reducing the number of short-haul flights, and imposing passenger duty on transfer passengers, there have been others that have proposed changes to airspace management and handling procedures.

|

| HEART1A concept proposed by Environmentally Responsible Air Transport (ERAT) that makes use of just two holding stacks, instead of the existing four. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)